For those of us with zero German, “Ulm” is a gift of a name. One crisp syllable. Easy to say, easy to remember. But—if you’re arriving by bicycle—may be not quite so easy to get in.

Our guidebook, published five years ago, helpfully warned of major construction works along the approach to Ulm. We assumed they’d be long finished.

We had not done our homework.

Ulm’s world-famous Minster, boasting the tallest church steeple in Christendom, took over 500 years to build. Construction began in 1381 and wrapped up in 1890, with a casual two-century pause somewhere in the middle while it transitioned from Catholic cathedral to Protestant minster. Renovations, which started in 2015, are scheduled to continue until 2030. Clearly, Ulm takes the long view.

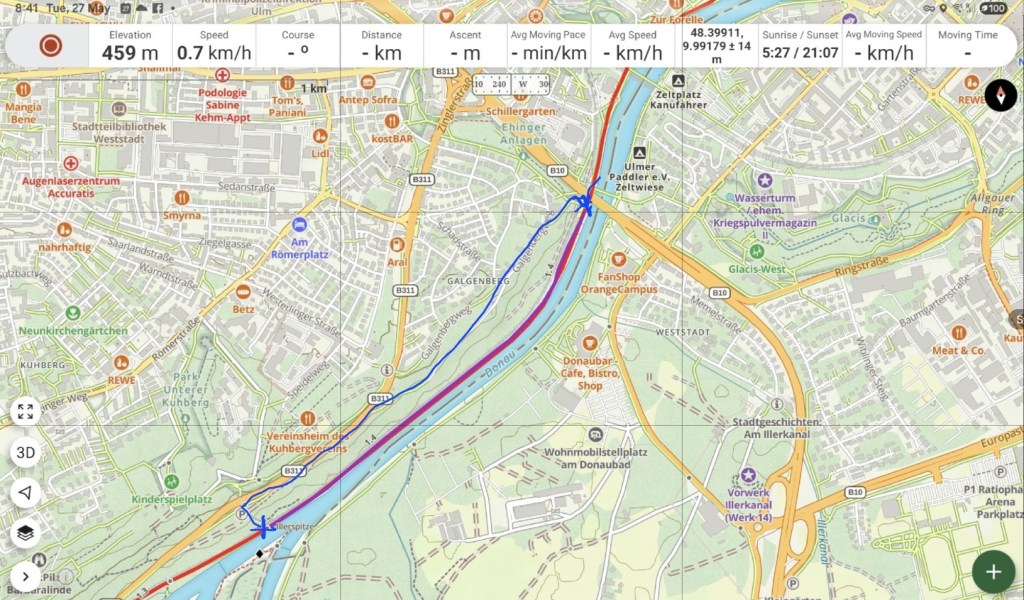

So we shouldn’t have been surprised when, on the outskirts of town—with that soaring steeple within sight—the Danube Cycle Path ran into a literal wall of red road signs, metal fencing, and firm authority.

We tried the usual tourist tactics—confused pointing, hopeful shrugging, miming alternative routes—but were met with a firm “NEIN” and some impressive hand gestures that strongly suggested, go away.

So we turned around. Slowly.

Looking for… anything, really. A path. A clue. Divine intervention.

About a kilometre back, we spotted what might once have been a railway underpass, now reclaimed by moss and mystery. It didn’t appear on any map. It could lead to the road which we could hear somewhere overhead, or to Narnia. CS (Cycle Sidekick, not Lewis) went to investigate on foot. I stayed back with the bikes and a brave face.

Moments later, three Germans on sturdy electric bikes rolled up. I launched into an impromptu game of charades:

Lost Tourist 😞 → Blocked Road ✋🤚 → Detour? 🧐

The man in the group nodded in quiet understanding and, without a word, disappeared into the same tunnel where CS had vanished minutes earlier. We three not-so-young women looked at one another. New to the etiquette of cycle touring, I wondered if this is how route-finding works here: when in doubt, follow the most recent person who disappeared.

Just then, a much younger man emerged from the same underground passage where two older ones had disappeared, and began speaking to one of the German women in gestures scattered with sort-of English words. She looked puzzled: why would this man think she was married to a lost Australian on the other side of the rail track?

Thankfully, pretty soon, both husbands (hers and mine) reappeared. Mistaken identities were sorted and better still, we now appeared to have a way forward.

With no more ceremony, the young man grabbed my bike, still laden with two panniers and hauled it up some 30 crumbling steps of the underpass and onto a back lane somewhere above ground.

We barely had time to thank him before he zipped back down to help the two other women with their far heavier e-bikes. Three lifts, three zips, and he was gone—vanished back into the tunnel like a character from a cycling fairy tale.

Obviously he was a ‘track angel’: those miraculous creatures who appear whenever you are faced with insurmountable problems, on a long road (whether hiking or riding) and disappear before you can whip out your camera and take a photo. If you have not met one, that is only because you have not needed one yet.

But it wasn’t just him. All week, cycling through Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, we’ve been met by unexpected kindness. The sort that steadily dismantles the cliché you’ve learnt about German formality.

Unexpected, perhaps because the stereotypes are so deeply embedded. Germans, you are told, are efficient, punctual, law-abiding…no one said they were funny, warm, generous.

Early in the week, a young German cyclist had said to me wistfully, “I really want to visit Australia. Everyone there is so friendly.”

“Germans are friendly too!” I protested.

He remained unconvinced: “Maybe to foreigners. But to each other? We are… quite strict.”

We all know, of course, that such generalisations can only be wrong. That the real story is told in individual moments of engagement, in snippets of conversation. Like when the owner of Fridingen’s Donauback Bakery, insists on giving us a bag of rolls—“German bread, to try!”—and refuses every attempt to pay. When the youngest monk in Beuron’s ancient monastery shares his passion for the art movement born within the walls of the cloister. Or the retired linguist who once cycled this same path we are on, gently unravels the highs and lows of our own upcoming route. And all the faster cyclists who stopped to explain a sign, translate a menu, or point us gently on our way.

And just when we thought the surprises were done for the day, the woman at Ulm’s tourist centre beamed and said, “Oh, but you must stay extra day! Deutsches Musikfest starts tomorrow.”

There was free music, everywhere—from the ethereal organ concert under the soaring ceiling of the Minster to brass bands bouncing off the cobbled streets round the old city square. You can’t say no to such gifts: from the river, its shores and its people!!

The Danube has carried us through more than towns and meadows—it has been a river of goodwill.

So, with full panniers and bellies full of bread, we wobbled out of Ulm—serenaded by good memory, and carried by hearts full of kind vibes, a little pedal power and just a dash of curiousity about what we might loose and gain around the next bend of this river.