Budapest is the perfect place to end your Danube ride — scenic, grand, and with the Buda Castle practically built for selfies. But cycling into the city in the middle of a weekday feels more like a survival challenge: dodging potholes, trucks, and a variety of other motorised machines.

Let’s backtrack to Bratislava, where the last blog left off.

The collective wisdom of the cycling community says that as you head east of Bratislava on the EuroVelo 6, both the path and the traffic get worse. While broadly true, the experience is less a steady slide into chaos and more of an erratic patchwork — mostly you’re cruising, interspersed with (thankfully, brief) periods of handle-bar clenching anxiety.

Choosing your route is part strategy, part luck as any guidebook or route map becomes outdated quickly, as upgrades and diversions happen on both sides of the Danube — in Slovakia and Hungary.

Our first foray into Hungary — across the bridge from Komárno (Slovakia) to Komárom (Hungary) — was brief and traumatic. That bridge was not built with cyclists in mind, unless the goal was to weed out the faint-hearted. We promptly retreated and stayed on the Slovak side for as long as we could.

The route we followed — over 300 kilometres through Slovakia — was mostly on flood levees: easy riding, low traffic. Signage is minimal, but there’s little risk of getting lost. There isn’t much spectacular scenery to distract you, and any deviation from the levee quickly lands you on potholed back roads or highways crammed with impatient motor vehicles. Self-preservation has a way of focusing the mind.

Štúrovo, our final stop in Slovakia, is unlikely to feature in many tourist brochures. Just across the Danube, its glamorous Hungarian twin, Esztergom, boasts domes, spires, and postcard charm. The vast grey-green dome of the basilica (colour-matched to the Danube?) pulls in tourists on riverboats named after English poets!

Štúrovo’s only drawcards are its budget hotels and the wonderful view of Esztergom castle as you cycle in — though the town could be vastly improved if it simply learnt to put its skeletons in cupboards, instead of leaving them strewn along the main street.

Shortly after Štúrovo, the EV6 veers onto main roads for several tense kilometres. And then — miraculously — a perfectly sealed cycleway reappears just before the new Ipolydamásd Bridge, marking the border into Hungary. We missed the cycleway on the bridge, as did the bemused Frenchman on his way to the Black Sea, whom I ran into while backtracking to photograph the “Hungary” sign.

While we were fumbling with phone maps, the Swedish Cyclist swung in, oozing local knowledge. Yes, he assured us, we were on the right path, and yes, it would take us straight into Budapest.

We didn’t quite follow his advice. Instead, we crossed the river again to visit the historic town of Visegrád – our first overnight stop in Hungary. It has the works: river, hilltop castle, stunning views from our boat-hotel.

Next day, we missed a turn and got lost on Szentendre Island. Luckily, it turned out to be the perfect place to get lost: we met an English-speaking chef who not only guided us to the ferry but also gave us a list of must-try Hungarian foods, which we dutifully did as soon as we got into town!

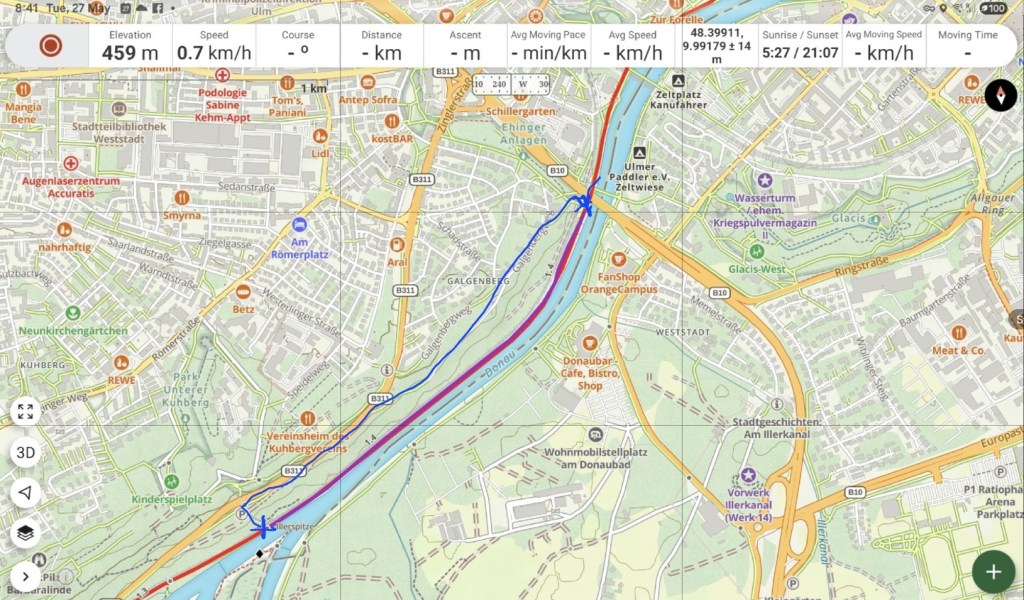

Eventually, trusting in the Swedish cyclist’s ‘local knowledge’ of Hungary, we rejoined the smooth, well-marked path toward Budapest. It was perfect — until it wasn’t. About 10 kilometres before the city, the route dissolved into an industrial hinterland where potholes ruled both road and pavement, and trucks roared by uncomfortably close. The “cycle path” seemed to be whatever flat surface you could ride on. We saw just two other cyclists in this stretch, both carrying what appeared to be the detritus of their lives: bikes festooned with ripped plastic bags, bulging with cans, bottles and rags. It was a throwback to my childhood in Delhi, where adults cycled only if they had no other choice.

The cycle route into Budapest is not well marked. Wth various electronic maps CS (Sidekick) — somewhat miraculously — got us into the peace and shade of Margaret Island, which fully earns its title as the Lungs of Budapest. Our sigh of relief was short-lived. A final dash through traffic on busy main roads, where some drivers seemed unaware that cycle lanes are meant only for cycles, brought us to Budapest city centre— and the end of our journey.

1,300 kilometres from the source of the Danube, in 38 cycling days — more if you count sightseeing on rest days, and more still if you count the times we got lost and had to retrace our steps. But who’s counting?

It feels good to have completed our first-ever long-distance ride at 70. Proves you can indeed teach old dogs new tricks.

And now, the Awards:

And we have just started planning our next cycle trip… all suggestions welcome!